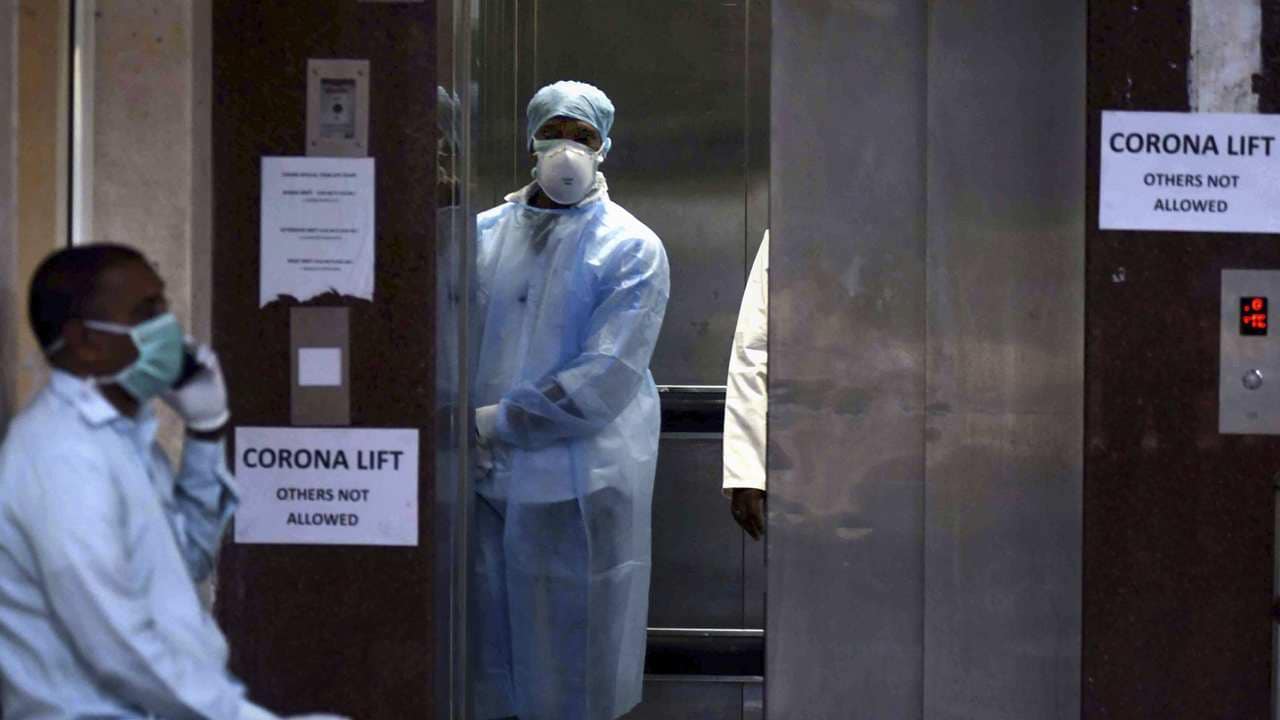

Health

COVID-19 offers unique opportunity to transform Maharashtra's private healthcare sector, introduce minimum standards of operation

India’s private healthcare is among the most under-regulated in the world, and for the larger part after independence, there has been no overarching attempt to regulate minimum standards and rates of services.

Dr Soham D Bhaduri Last Updated:May 31, 2020 20:36:50 IST

The Government of Maharashtra on 21 May decided to ‘take over’ 80 percent of private hospital beds in the state by capping procedural and other charges for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients. It also admonished charitable hospitals to strictly comply with the legal obligations pertaining to treating poor and economically weaker section (EWS) patients. This has been done both in view of the limited public sector capacity to handle COVID-19 cases as well as to prevent economic hardship during the pandemic. This decision has been highly welcomed.

There are two remarkable things about this decision that are also unprecedented. First is that the state has explicitly admitted to exorbitant fees being charged by the private healthcare sector. The second remarkable thing is that by imposing price control, the government has not elicited vociferous opposition from the private sector. These would have been impossible had it not for the crisis begotten by the pandemic.

But while the crisis has brought to the fore both overcharging and under-regulation in private healthcare sector as acute problems, it is impossible to deny that these are long-standing and deeply-rooted issues that for decades have been neglected by the state and have impaired healthcare provision, mainly to the poor.

Related Articles

Maharashtra police file case against Dean, doctors of Nanded hospital over death of 31 patients

12 killed, 23 injured as speeding mini-bus rams container on Maharashtra Expressway

Also, to discuss these problems merely in the context of COVID-19 would be to trivialise these deeper dimensions, while disregarding the opportunity for pushing long-term reforms that presents before us today.

Let us first consider the case of charitable hospitals, registered in Mumbai under the Bombay Public Trusts Act, 1950. Such state-aided hospitals receive various subsidies and exemptions, and until the 1980s largely served on a genuinely charitable basis delivering affordable healthcare. In the following years, many of them adopted market-like practices and instances of non-compliance with minimum obligations became rife.

A study noted that between January 2009 and December 2011, only one charitable hospital in Mumbai spent more than 10 percent bed-days for poor patients. Trivedi (2013) noted accumulation and gross underutilisation of funds set aside for poor patients by charitable hospitals in Pune. Hooda (2015) noted charitable hospitals in India to be largely urban-centric in location, defying the expectation that they would serve underserved pockets. He also noted that the per worker and per enterprise Gross Value Added (GVA) of these hospitals were higher than that of for-profit hospitals, indicating profit maximisation.

India’s private healthcare is among the most under-regulated in the world, and for the larger part after independence, there has been no overarching attempt to regulate minimum standards and rates of services.

The central Clinical Establishments Act (CEA), 2010, was the first major attempt in this direction. The act has been enacted in 11 states, but none can boast of the strong implementation of its provisions. Interestingly, Maharashtra has not adopted the act. Instead, there is the Maharashtra Nursing Homes Registration Act (MNHRA), 1949, but it lacks provisions for rate regulation and doesn’t apply to small establishments like clinics and dispensaries. Even this minimum Act has been grossly under-implemented.

The organised medical lobby has time and again successfully thwarted major attempts to regulate the private sector, citing a threat to small clinics and nursing homes, rise in bureaucratic corruption, and possible increase in healthcare costs. A recent example is that of Haryana, where a decision to enforce CEA in 2017 attracted massive opposition from the state Indian Medical Association (IMA), restricting its scope to larger hospitals with more than 50 beds. But, particularly noteworthy is how it has blocked attempts at rate regulation, both nationally and in Maharashtra.

Phadke (2016) notes that as part of a sub-committee constituted under the central CEA rules (2012) to decide rate ranges for services, the IMA strongly opposed the very idea of rate regulation. In Maharashtra, the medical lobby has vehemently opposed adoption of the central CEA. At least three attempts were made after 2012 to bring a Maharashtra-specific CEA, and rate-regulation under such an act has been fiercely opposed. Presently, the fate of either a Maharashtra CEA or a modified MNHRA remains in limbo.

It is easy to understand that where millions live in abject poverty, especially when the private sector has about 80 percent share in healthcare provision, absence of even minimum oversight and regulation pertaining to rates charged and minimum requirements has jeopardised healthcare for legions of people over decades. The constraints and damage inflicted due to COVID-19 would pale in comparison.

Once in place, institutions often tend to develop along path-dependent trajectories. Over time, these trajectories become entrenched and difficult to alter, except during crises and upheavals. Such crises open windows for undertaking change because resistance is partially overcome.

The under-regulated private sector is so deeply entrenched that the slightest whiff of regulation appears alien and attracts strong opposition. It has always thwarted acts such as the CEA during times of normalcy. The current COVID-19 crisis has permitted temporary provisions for rate regulation and oversight of charitable hospitals in Maharashtra. It is only fitting that after the pandemic recedes, similar provisions carry over and are institutionalised into permanence, albeit following a fair and consultative process.

We must remember that following the COVID-19 health catastrophe, public support for such pro-public health measures will be at the highest. All it will take is enough political will to negotiate the diminished shoals of private sector interests.

The scourge called COVID-19 has brought along a unique opportunity for the Maharashtra government to introduce reforms that are long due and can greatly enhance healthcare equity and access in the state. Whether to utilise it or imprudently pass it up will lie with the state government.

The author is a Mumbai-based doctor, healthcare commentator, and editor of The Indian Practitioner, a foremost peer-reviewed medical journal