NATURE

Eight bears: Mythic past and imperilled future

by Gloria Dickie (Norton £25, 272pp)

There are eight species of bear around today. Can you name them?

I got as far as black bear, brown bear, polar bear and panda bear, with vaguer notions of a spectacled bear — and what about grizzly bear? Is that a species?

The actual list of bears that share our planet came as a surprise. Grizzly bears aren’t a separate species, they are merely a sub species of brown bear.

The same goes for those mighty Kodiak bears of Alaska, which can weigh up to a tonne, and stand at three metres high on their hind legs. Yikes.

The other species that might have eluded you are the sloth bear of India, a hopeless name, because it isn’t a sloth at all, it’s just a bear — and one of the most dangerous of all; the spectacled bear that lives in Ecuador and Peru; and the sun bear and moon bear, or Asiatic black bear, of South-East Asia.

Pandas generally just prefer nibbling bamboo shoots and sleeping to the arduous business of producing more pandas

In her wonderfully eye-opening and compelling account, Dickie starts by considering why the bear is so appealing to the human imagination.

Other animals may be charismatic and beautiful, but few children go to sleep at night cuddling a toy eagle or leopard.

Yet there are any number of fictional bears: Winnie the Pooh, Paddington Bear, Rupert Bear . . .

‘I’ve yet to encounter a tale featuring a villainous bear,’ says the author, while sinister wolves are everywhere.

It’s hilarious to learn that in the original Goldilocks, the intruder is an ugly, foul-mouthed old woman, and the three bears are gentle souls who aren’t sure how to get rid of her.

This fondness for bears also appears in many tribal cultures, where the bear is referred to as grandfather, or a teacher of wisdom. If you’re hungry in the forest, say some, just eat what the bear eats.

There’s an intense sense of bear-human likeness. Yet the modern world is proving grim for these amazing creatures, along with so much other wildlife.

By the end of this century, there may be only four species left. What a failure this would be for them and us. If we revere them so much, they are going to need a great deal more protection and wild space to roam.

Dickie explains that pandas are simply too lazy to fight with any other species for calories

Yet where bears are tolerated more, results can be mixed. In the U.S., black bears are protected and their numbers have rocketed. Now, they are moving into the cities, foraging from wheelie bins.

One bear that wandered far too close to an elementary school in Colorado and had to be shot, was found to have enjoyed a recent diet of ‘two steaks (still in their wrappers), pasta, potatoes, eggs, avocado, paper towels, apples, lunch meat and carrots — all salvaged from nearby dumpsters’.

In the longer-term, this may produce semi-urbanised bears just as fat and malnourished as many people are today on their diet of fast food and junk.

The spectacled bear is, of course, Michael Bond’s Paddington Bear. They do love eating fruit, up in the trees in their native cloud forests, but ‘there is no record of a spectacled bear ever eating a marmalade sandwich’.

A shy and elusive creature, the author herself fails to spot one on a field trip and they remain an appealing mystery.

Far more alarming is the Indian sloth bear, which is responsible for more human fatalities than any other species, attacking some 150 people a year. Short-sighted and ill-tempered, they will go for anyone who startles them on a forest path.

They may be so jumpy, naturalists think, because while other bears occupy the top of the food chain in their environments and can generally relax, sloth bears live alongside ferocious hunters and stalkers such as leopards and tigers.

A sloth bear’s only defence is ‘to explode in a flurry of fur, stumpy teeth and claws when threatened’. They’re not exactly blessed in the looks department either, with ‘loose protruding lips’, often dribbling at the mouth.

The Asiatic black bear, or the sun bear and moon bear, is native to South-East Asia

There’s a very funny chapter on panda bears. They eat almost solely bamboo, which isn’t very nutritious but, because no other animal really wants it, it’s easy pickings.

Pandas, ‘one of the animal kingdom’s laziest members, can’t be bothered to fight with any other species for calories’.

Sex is a bit of an effort, too, which is partly why their numbers are so perilously low.

Captive pandas have been variously encouraged with doses of Viagra, ‘panda pornography’ and even adult sex toys, but to no avail.

They generally just prefer nibbling bamboo shoots and sleeping to the arduous business of producing more pandas.

More disturbing by far is the fate of the sun bears of Vietnam and China, which are ‘farmed’ for their bile: another of those barbaric ‘traditional medicines’.

Farmers cut into the bear’s liver and insert a needle to drain off the bile. ‘Animal welfare advocates who have witnessed this farming method say the bears “moan and quiver” throughout the process.’

Bears often succumb to infection from surgical wounds. There are some 20,000 bears in China’s bile farms, says Dickie. It’s legal there, and worth $1 billion (£790million) a year.

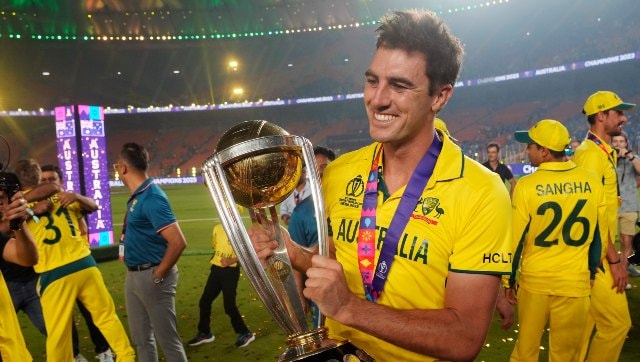

A grizzly bear, which is a sub-species of the brown bear, sits proud at a wild game park

Bears, like many other wild animals, may attack a human because they are startled, afraid, cornered or hungry.

But for industrial-scale cruelty like this, it is shameful to say, you really need human beings.

Will we learn to live alongside all our bear species, protect them, and see them returning to healthy numbers?

Or will we still demand the entire planet for ourselves alone, leading to further extinctions — and eventually our own, too?

Dickie concludes: ‘Losing bears would mean we lose a beautiful and complex relationship. We would lose a grandfather, an uncle, a mother, a medicine man, and a teacher. And in some ways, we would lose a part of our own wildness.’